the Dative Case in Russian

Are you thinking about learning the Dative Case in Russian?

Just take a look at some of the situations in which it is used:

01) To indicate the indirect object in a sentence;

02) To talk about feelings and emotions;

03) After specific prepositions;

04) To express age;

05) To say what you like;

06) To say what you need.

As you can see, just by learning the Dative Case, you will be able to communicate in Russian on a wide variety of topics, so it’s totally worth learning it.

To make things easier, I will divide this lesson into 4 parts:

2) The main situations in which the Dative Case is used;

3) Adjectives in the Dative Case;

4) Possessive Pronouns in the Dative Case.

All the tiles in blue have links. If there is any subject you would like to study first, you can click on it and go straight to that part of the lesson.

In this lesson, we won’t talk about plural nouns and adjectives in the Dative Case because we already have complete lessons about this subject here at Mighty Russian.

If you already know when to use the Dative Case and how it’s used in the singular, you can go straight to the next lesson:

- Dative Case in the Plural

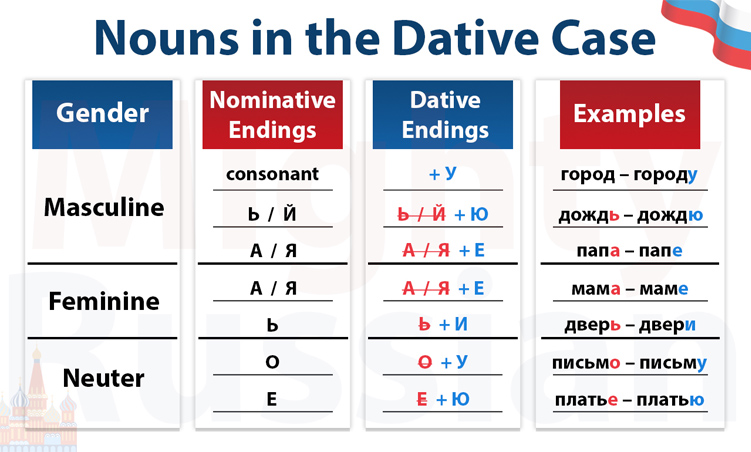

Nouns in the Dative Case

When using the Dative Case, you’ll have to change the ending of the nouns. Nouns in the Dative Case can have 4 different endings: “Е”, “У”, “Ю” and “И”.

Note that the ending of a noun depends on its gender.

The concept of gender in Russian is very simple to understand, but if you are not familiar with it yet, make sure to check out our complete lesson about this subject clicking here.

Let’s take a look at when we use each of these endings.

1) Letter “Е”:

When a noun ends in “А” or “Я”, replace these letters with “Е”:

мама – маме (mother)

машина – машине (car)

тётя – тёте (aunt)

дедушка – дедушке (grandpa)

2) Letter “У”:

When a masculine noun ends in a consonant, add “У”:

стол – столу (table)

город – городу (city)

студент – студенту (student)

врач – врачу (doctor)

When a neuter noun ends in “О”, replace “О” with “У”:

окно – окну (window)

письмо – письму (letter)

дело – делу (business)

тело – телу (body)

3) Letter “Ю”:

When a neuter noun ends in “Е”, replace “Е” with “Ю”:

море – морю (sea)

поле – полю (field)

платье – платью (dress)

When a masculine noun ends in “Й” or “Ь”, replace these letters with “Ю”:

словарь – словарю (dictionary)

дождь – дождю (rain)

музей – музею (museum)

герой – герою (hero)

4) Letter “И”:

When a feminine noun ends in “Ь”, replace “Ь” with “И”:

ночь – ночи (night)

площадь – площади (square)

дверь – двери (door)

When a feminine noun ends in “ИЯ”, replace only “Я” with “И”:

лекция – лекции (lecture)

станция – станции (station)

версия – версии (version)

And those are all the endings you have to memorize.

I know it can be scary to look at all these rules, but actually, you don’t have to learn all of them at once.

Just try to practice your Russian on a regular basis and you will naturally memorize all these endings.

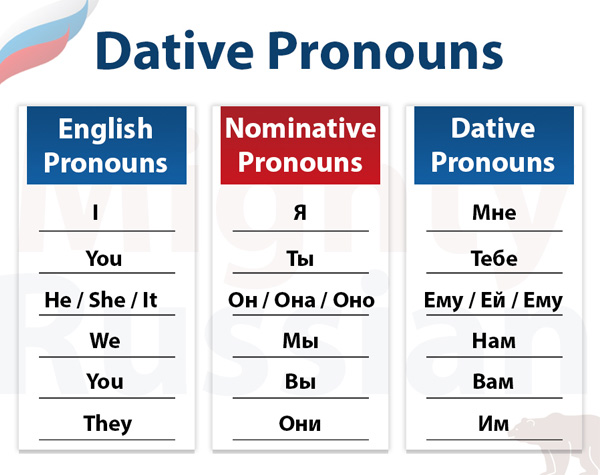

Besides the nouns, we also have Dative Pronouns. Make sure to learn them as well.

Now let’s take a closer look at the situations in which we use the Dative Case.

When to use the Dative Case in Russian

These are the 6 most common situations in which the Dative Case is used:

1) The Dative Case to indicate the Indirect Object;

2) Expressing feelings and emotions with the Dative Case;

3) Prepositions that require the Dative Case;

4) The Dative Case to talk about age;

5) The verb “нравиться / like” with the Dative Case;

6) The Dative Case to say that someone needs something.

Let’s learn each of them individually!

01) The Dative Case to Indicate the Indirect Object

In Russian, the indirect object of a sentence is indicated by the Dative Case.

An indirect object is usually a person to whom or for whom something is done.

To make things easier, let’s take a look at a simple sentence:

Peter gives a book to Masha / Питер даёт книгу Маше

Can you guess what is the indirect object in this sentence?

If you’re having difficulty with it, try and ask “To whom or for whom is the action done?”

As you can see, the book is given to “Masha” and, therefore, “Masha” is the indirect object.

So, in Russian, “Masha” is in the Dative Case.

Питер даёт книгу Маше

Маша / Маше

If it’s already clear to you what an indirect object is, feel free to move on to the next usage of the Dative Case.

But if you’re not entirely sure about it, here are some more examples:

The parents buy ice cream for their son / Родители покупают сыну мороженое

Let’s ask the same question. “To whom or for whom is the action done?”

To the son, right?

So “the son” is the indirect object and, in Russian, it takes the Dative Case.

Родители покупают сыну мороженое

сын / сыну

One more example:

I brought food to the dog / Я принёс еду собаке

To whom or for whom is the action done?

To the dog. So “the dog” is the indirect object and, in Russian, it takes the Dative Case.

Я принёс еду собаке

собака / собаке

Simple, right? Let’s go to the next situation!

02) Expressing Feelings and Emotions with the Dative Case

The way we express feelings and emotions in Russian is a little bit different from the way we do it in English.

In English, we make sentences in the following way: subject + verb to be + adjective.

For example:

I am sad

In Russian, however, we simply use a noun or a pronoun in the Dative + an adverb that represents the emotion.

Let’s take a look at some examples:

Девочке грустно (The girl is sad)

Ребёнку интересно (The kid is interested)

Им холодно (They are cold)

Note that in all the sentences, the person is in the Dative Case (in red).

03) Prepositions that are used with the Dative Case

There are two Russian prepositions that are always followed by the Dative Case: “К” and “ПО”.

Let’s take a look at each of them.

The preposition “К” normally means “towards” and sometimes “to”.

For example:

Вчера я ходил к врачу (Yesterday I went to the doctor)

Завтра мы поедем к бабушке (We will visit Granny tomorrow)

The preposition “ПО” has several meanings:

01) It can mean “about” or “on” when something is related to a particular subject or area.

For example:

Это учебники по истории (These are textbooks on history)

Он написал статью по биологии (He wrote an article about biology)

02) It can mean “along” or “on”. When something is moving along or on some surface (note that you can use “ПО” in this meaning only if there is movement).

Человек идёт по дороге (The man is walking along the road)

Паук ползёт по стене (The spider is crawling along the wall)

03) It can also mean “over”, “on” or “by” when you talk about the means you use to do something.

Я говорю по телефону (I’m talking on the phone)

Мы болтаем по Скайпу (We are chatting by Skype)

Probably you have noticed that all the prepositions have many different translations.

But if you pay attention, you will notice that the meaning is only one.

The best way to learn these prepositions is not by memorizing their translation but by analyzing the examples and understanding what they mean.

04) The Dative Case to talk about age

This situation is very simple.

Whenever you say how old someone or something is, you just need to put the noun or the pronoun into the Dative Case:

Мне 20 лет (I am 20 years old)

Ребенку 2 года (The kid is 2 years old)

Дедушке 70 лет (Grandpa is 70 years old)

05) The verb “нравиться / like” with the Dative Case

This usage of the Dative Case is also quite simple, but you will have to learn and get used to a new structure here.

When you say that somebody likes something in Russian, you use the verb “нравиться” and “the person who likes” is always in the Dative Case.

For example:

Ему нравятся собаки (He likes dogs)

Питеру нравится ходить в спортзал (Peter likes going to the gym)

Мне не нравятся кошки (I don’t like cats)

Раньше ребёнку нравились мультики (In the past, the kid liked cartoons)

Now, you may have noticed that the sentences with the verb “нравиться” are a bit different from sentences with other Russian verbs.

That’s because we conjugate the verb “нравиться” according to the person or object that is liked and not the person who likes.

I know this can be very confusing for learners, so I made a complete lesson about all the possible ways to say “like” in Russian with the verb “нравиться”.

If you don’t know this subject yet, make sure to check out this lesson clicking here.

06) The Dative Case to say that someone needs something

To say that someone needs something, you will have to learn another structure:

“The person who needs” in the Dative Case + the word “нужно” + the person or object that is needed in the Nominative Case.

For example:

Мне нужны деньги (I need money)

Девушке нужно работать (The girl needs to work)

Ему нужна помощь (He needs help)

And these are the most common situations in which you will use the Dative Case. I advise you to focus on these situations at the beginning.

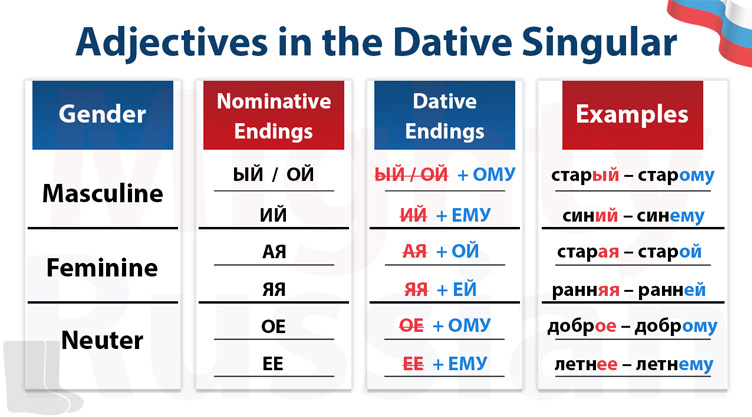

ADJECTIVES IN THE DATIVE CASE

Adjectives in the Dative Case are used in the same situations as nouns and take special endings.

The ending you’re going to use depends on the gender of the noun the adjective describes.

Let’s take a look at each gender individually.

ADJECTIVES IN THE MASCULINE

Replace the endings “ЫЙ” and “ОЙ” with “ОМУ”:

новый друг – новому другу (a new friend)

большой дом – большому дому (a big house)

молодой человек – молодому человеку (a young person)

Replace the ending “ИЙ” with “ЕМУ”:

синий костюм – синему костюму (a blue suit)

хороший друг – хорошему другу (a good friend)

горячий чай – горячему чаю (hot tea)

Note that when the last consonant of the adjective is “К” or “Х”, the adjective takes the ending “ОМУ” instead of “ЕМУ”:

русский человек – русскому человеку (a Russian person)

тихий вечер – тихому вечеру (a quiet evening)

маленький ребёнок – маленькому ребёнку (a little child)

ADJECTIVES IN THE NEUTER

Neuter adjectives take the same endings as masculine adjectives.

Replace the ending “ОЕ” with “ОМУ”:

новое платье – новому платью (a new dress)

большое окно – большому окну (a big window)

тихое море – тихому морю (a quiet sea)

Replace the ending “ЕЕ” with “ЕМУ”:

хорошее лето – хорошему лету (a good summer)

синее небо – синему небу (a blue sky)

летнее платье – летнему платью (a summer dress)

ADJECTIVES IN THE FEMININE

Replace the ending “АЯ” with “ОЙ”:

новая квартира – новой квартире (a new apartment)

русская девушка – русской девушке (a Russian girl)

большая комната – большой комнате (a big room)

Note that when the last consonant of the adjective is “Ч”,“Ш”, “Щ” “Ж” and “Ц” and the last syllable is NOT stressed, the adjective takes the ending “ЕЙ” instead of “ОЙ”:

свежая капуста – свежей капусте ( fresh cabbage)

горячая вода – горячей воде (hot water)

хорошая сумка – хорошей сумке (a good bag)

Replace the ending “ЯЯ” with “ЕЙ”:

зимняя ночь – зимней ночи (a winter night)

синяя куртка – синей куртке (a blue jacket)

ранняя весна – ранней весне (early spring)

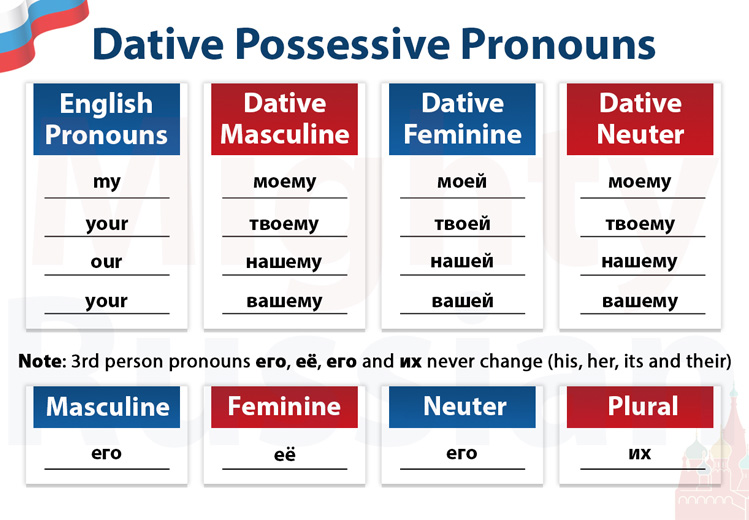

POSSESSIVE PRONOUNS IN THE DATIVE CASE

The Possessive Pronouns that you are going to use in the Dative Case are as follows:

You will use these pronouns in the same situations that you learnt about earlier.

For example:

Я звонил твоему брату вчера (I called your brother yesterday)

Нашей маме нужно отдыхать (Our mom needs to rest)

Сколько лет твоему папе? (How old is your dad?)

And that’s it guys.

Now you can use the Dative Case confidently whenever you speak Russian.

I hope everything got clear, but if you have any questions, just leave them in the comments below.

I will be very happy to help you!

Спасибо большое

Здравствуйте дарагоя учительница

Я принимаю решение что я ещё раз выучу ваши саит. Это потому что мне надо писать правило по-русски.

Я всегда ценю вас.

Пасиб.

Да да, по моему мнению это натуральный что иногда мы чувствуем не успехов.

Поэтому я бросил вычет по-русски.

Но с сожалению мне очень рад что ещё раз я собираюсь выучить

по-русски по очень строгий.

Я бологодарю вас дарагоя учительница Настя.

🙏🙏